Putting

on a Reenactment - Part Two

Putting

on a Reenactment - Part Two

Part Two: Researching for the Reenactment Script

In Part One, I wrote about events leading up to the decision to do a reenactment of an 1883 shootout on Main Street that happened in my small Central Texas hometown and the history behind it.

Some of the committee members had been in the previous reenactment years earlier that showcased only the big shootout. Since this was the 150th anniversary, and there is so much automatic and vehement opposition to anything that smacks of vigilantism in today’s world, I wanted to highlight some of the events that led up to the shootout. (Someone reminded me of the movie “The Ox-Bow Incident” on Facebook; I retaliated with the hanging scene from “Lonesome Dove.” I’ve never heard anyone complaining that the oppressed Mexican villagers shouldn’t have hired The Magnificent Seven either.)

I made it plain if I was to write it, the reenactment script would have to be my interpretation, but I would like to read the previous script to see what they had done. I was given a copy, and as soon as I read the short script, I knew what had caused the rift in the historical society and the museum curator’s adamant opposition to doing another one.

A writer from Canada had become enamored with the history of our small town and had been instrumental in putting on the reenactment. She, in turn, had come under the influence of a descendant of one of the men hanged by a group of vigilantes after the murder of a deputy sheriff on the trail of a killer and a vicious attack on a local farmer and businessman. After hearing of her great-grandfather’s demise at the end of a rope in a town she had barely heard of, she had set out to prove his innocence. Her ex-husband had been a public defender, and she knew only too well how many times the wrong man was arrested and plea deals were cut. Both women were nice and extremely personable. The museum curator, who had lived in the town 50 plus years but had not grown up there, fell under their spell and endorsed the revisionist history they came up with, going so far as having a smiling photo and an article placed in the neighboring local newspaper endorsing it.

In their version, the hanged men were innocent, and their relatives had been goaded into a lopsided gunfight with the vigilantes downtown. The vigilantes were supposedly secretly selling meat from stolen cattle, and it was all a big coverup to keep them from getting exposed.

It sounds like a great plot for a book, but it went against every story we had grown up listening to. I could see now why the curator was so against bringing it up again and was desperate to squash our efforts. She must have been blistered by people saying, “Whoa! It didn’t happen that way.”

But did it? I read everything I could about the Notch-cutter gang and the Vigilantes, most of it repeating what somebody else had written. After the shootout, the sheriff had arrived and arrested everyone. Eventually, only one man was tried and those notes had disappeared from the courthouse. But the examining trial notes were available online, and I read through those carefully and repeatedly, always keeping in mind the conditions of the time. These were men telling things under oath that could cause them to lose their homes or be waylaid and killed.

The wife of one of the supposed outlaws wrote an erudite and scorching condemnation of the two men who killed her husband, protesting he had gone to town without a gun, a knife, or any weapon whatsoever. If she is to be believed, her husband was completely innocent.

And these two men, wealthy store owners, had reputations of being dangerously tough.

However, in 1883, a woman’s life and place in society, and more importantly, that of her children, rested on her husband’s reputation. Although I admired her loyalty and ability as a writer, I could not in good conscience take her testimony as fact.

Four of the six men who survived the fight with the two supposed vigilantes in a gun battle proclaimed their innocence. They said they thought the two men were their “friends” and could not imagine why they had wanted to shoot it out with them. Hmm, your relatives are hanged; you go to town the next day and learn of it; you drink whiskey in a saloon stewing about it, and then you walk across town to the two men you hold responsible for it, yet you claim it was all a friendly visit? Even trying to keep an open mind, it was too much to swallow.

In addition to their implausible protests, there was their other testimony. While the two supposed vigilantes gave thorough descriptions of their movements and the actions of others before and during the shootout, the testimonies of the four supposed outlaws were vague and lacking in details.

But the descendant of one of the hanged

men was an incredible historian. She collected information

like a hoarder collects trash. And she believed her ancestor

who was hung and the relatives involved in the subsequent

shootout to be innocent. I had to find out the truth.

Little has changed since this picture was taken except that the streets have been paved. All the buildings except the one on the right were built after the big shootout. The rest had been burned or torn down.

The

building at the far right in the picture is the Rock Front

Saloon built by John D. Nash and run by his sons Horace and

Oscar. It was also a stagecoach stop. Passengers from Austin

would ride the stagecoach to McDade to catch the train to

Houston. This saloon and others were hangouts for every sort

of criminal hoping to soak money from the railroad workers and

the ranchers and farmers who fed them.

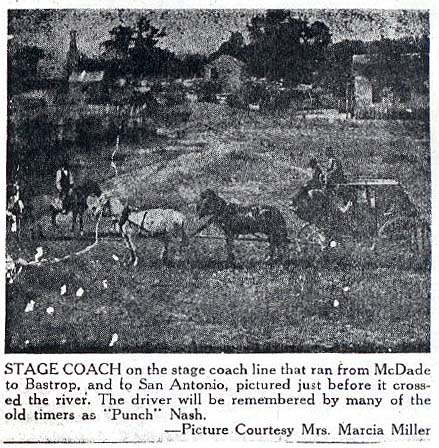

At right is a photo of the original stagecoach that ran from McDade to Bastrop and on to San Antonio. It was taken in Bastrop just before crossing the Colorado River.

John D. Nash’s Rock Front Saloon is now the McDade Historical Society Museum. They own the building next to it that we hoped to rent for various purposes during the 150th Celebration.

Coming up in Part Three: Sorting fact from fiction.

Books:

A broke Texas rancher risks all to drive longhorns through the wilds of West Texas to sell to the government in New Mexico, but he’s hindered by the feuding relatives and green cowboys he is forced to hire as drovers.

A BAD PLACE TO DIE and A SEASON IN HELL

Tennessee

Smith becomes the reluctant stepmother of three rowdy stepsons and

the town marshal of Ring Bit, the hell-raisingest town in Texas.

A little boy finds a new respect for his father when he helps him solve a series of brutal murders in a small Texas town.

A

rancher takes his nephews on an adventurous hunt for buried

treasure that lands them in all sorts of trouble.

Two

lonely people hide secrets from one another in a May-December

romance set in the modern-day West.

Short Stories:

WOLFPACK

PUBLISHING - "A

Promise Broken - A Promise Kept"

A

woman accused of murder in the Old West is defended by a

mysterious stranger.

THE UNTAMED WEST – “A Sweet Talking Man”

A sassy stagecoach station owner fights off outlaws with the help of a testy, grumpy stranger. A Will Rogers Medallion Award Winner.

UNDER WESTERN STARS - "Blood Epiphany"

A broke Civil War veteran's wife has left him; his father and brothers have died leaving him with a cantankerous old uncle, and he's being beaten by resentful Union soldiers. At the lowest point in his life, he discovers a way out, along with a new thankfulness. A Will Rogers Medallion Award Winner.

SIX-GUN JUSTICE WESTERN STORIES – “Dulcie’s Reward”

Seventeen-year-old

Dulcie is determined to find someone to drive her cattle to the

new market in Abilene.

"The decision to do a reenactment."

"Doing research for the reenactment."

"Sorting out the truth to make a historically accurate reenactment."

"Who's firing the guns?"

"Finding experienced reenactors."

"Organizing a reenactment - coming down to the wire."

"Rehearsing the reenactment."

"Show time!"