Putting

on a Reenactment - Part Three

Putting

on a Reenactment - Part Three

Part Three; Sorting Out the Truth to Make a Historically Accurate Reenactment

In Part Two, I wrote about a previous reenactment that had torn the local historical society apart. Was that version the truth, or the one I had grown up hearing?

The killing of Deputy Sheriff Isaac “Bose” Heffington has been shrouded in a mystery that has never been fully solved. He was shot in town on a November night as he searched for the perpetrator of the sadistic killing of two store clerks in his neighboring county. One man who went to trial for Heffington’s murder was found innocent when testimony revealed he simply did not have time to walk out of the saloon and accost him. In my family, legend has it that the real killer was one of my grandfather’s cousins. The deputy sheriff happened to be my grandmother’s uncle, so there was conflict between them about that. Theirs was a Romeo and Juliet romance gone sour.

In addition, there is confusion about what the deputy sheriff was doing in town. A signed statement by the sheriff of the neighboring county surfaced stating the deputy was not on official business, contradicting oral history. However, Heffington left a hefty insurance policy. It is easy to surmise that the sheriff, knowing the county was too poor to give the widow much assistance and fearing or knowing the insurance company would refuse to pay if his deputy had been on duty, signed a paper saying he wasn’t. Also, when the vigilantes held a secret meeting to discuss what to do about Heffington’s murder and the multitude of other crimes they had been subjected to, that same sheriff stood guard at the door to make sure no one got in who wasn’t supposed to be there.

Since it has never been proven, it seemed best that Heffington’s killer would remain nameless in the reenactment. Going into all that detail would be too time consuming and confusing.

And the men who were hanged, the ones whose death triggered the gunfight, were they innocent?

In the fall of 1883, a businessman had been shot, robbed, and left for dead. The bullet only creased his skull, and he escaped death by playing “possum.” Afterward, he told his business partners the names of the three men who had robbed him. Those partners, later to be involved in the shootout, advised him to remain silent. To go to the law and publicly put the finger on his assailants would be inviting death and destruction from the hands of the brutal Notch-cutters, so he pretended he didn’t know who had assaulted him.

A short time later, the vigilantes hanged three men. One article published years later stated they had been the attackers, but there was no written evidence at the time confirming it. However, the hangings came so close on the heels of the attack, it seems unlikely they weren’t connected.

The secrecy surrounding all this was incredible, even 100 years later, so it is not strange that there isn’t more concrete written evidence left behind. For protection, the vigilantes wore hoods and one needed a secret sign to enter their meetings. My great uncle had ridden his horse by four men on a limb coming home late one night from a dance in a neighboring community. When he told my great grandfather, he said, “Yes, and you better keep your mouth shut about it or you might be hanging from a tree next.” To have loose lips meant death, and it stayed that way for years.

In this instance, did the vigilantes hang the wrong men? One of the supposed hangmen was the great grandfather of a boy I went to school with. Godfearing and otherwise law abiding by all accounts, the old man always refused to talk about it, only saying, “We did what we had to do.” While this man’s great-grandson and I were in school together in the second grade, we had a teacher who was becoming increasingly abusive. The hangman’s son, now an old man, came to the school to visit and sat in the classroom the entire morning. At the time, I thought it was wonderful that he took such an interest in us. It was only years later when I remembered how nervous the teacher had been that day and how the abuse had lessened dramatically afterward that I realized the warning he had been giving her. So, I knew the family to be honorable, upright men who would do what they could to stop injustice. I could not believe their great-grandfather would hold the rope on any hanging unless he was sure of the guilt of the men in question.

But as time rolled on, conflicting stories surfaced, making it even more confusing. Even so, after careful research, I thought I knew the answer. But I questioned my judgement. Was I right in what I believed? I had to be sure in my mind before I put on a reenactment for prosperity in front of the entire town.

With the encouragement of another committee member, I approached a man I had known all my life. He and his family had owned a store downtown, and he had listened for years to all the stories the old men who gathered there told. I thought he would tell me tale after tale he had heard, and I looked forward to hearing them.

Instead, he said, “Vicky, we hung them, we shot them, their kinfolks left town, crime stopped, end of story.”

Seeing my disappointment, he added, “I’ve listened as those old men would tell one story to somebody and turn around and tell a different one to the next person who walked up.”

Crime stopped—end of story. Eventually, I felt a great relief and was most grateful for his confirmation of what I really already knew. A historian is like a junkie, always wanting more—and hoping to be the one to uncover something new. But I had a reenactment to write.

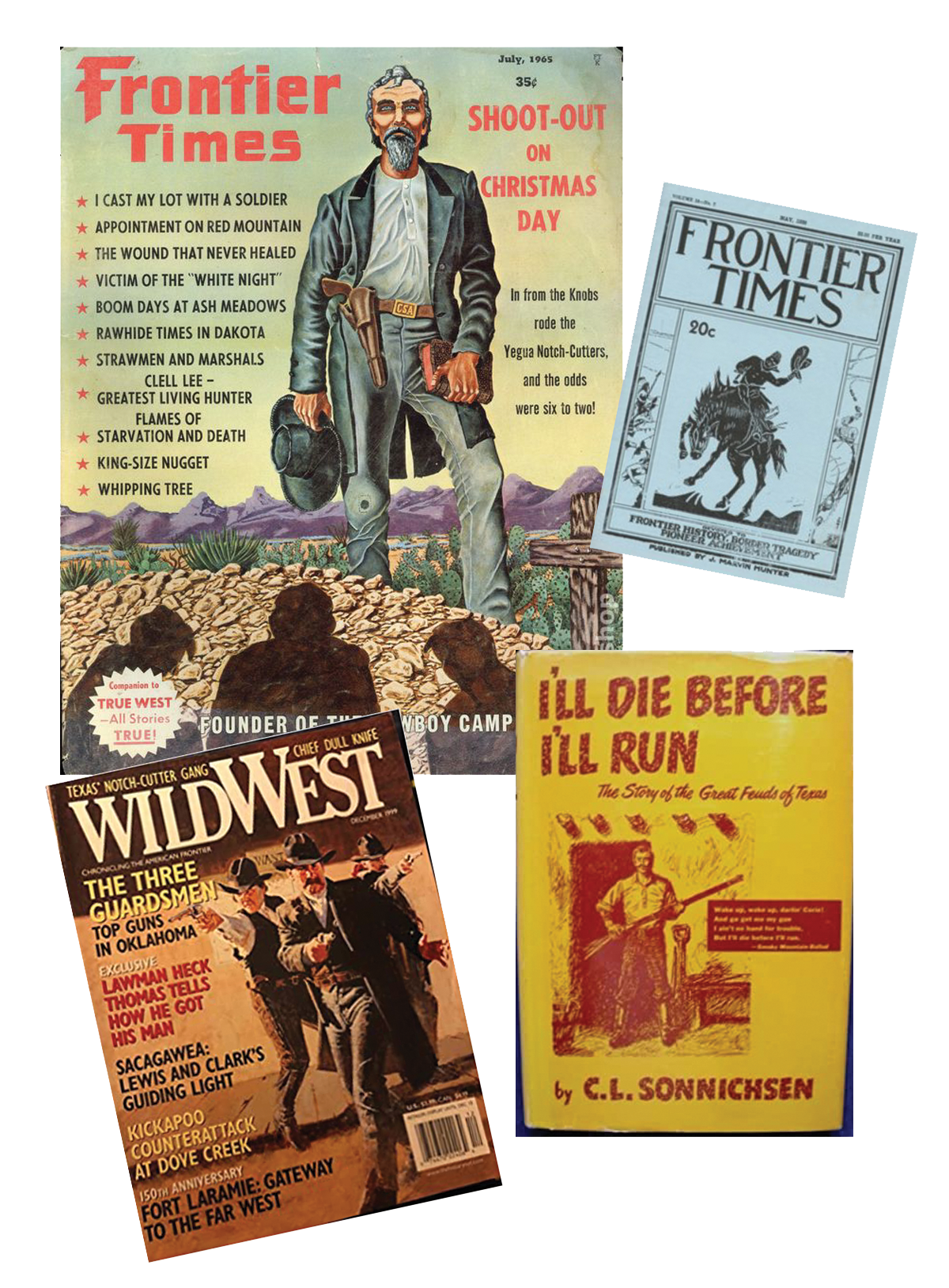

The events of the Christmas Day shootout have been written about many times. In the July, 1965 issue of Frontier Times, Luckett Bishop, Sr., a Texas Ranger, wrote that he wished to set the record straight about the events that happened when his father, Tom Bishop, and his father’s business partner, George Milton, were drawn into a gun battle with the six friends and relatives of the Notch-cutters who were hanged the evening before. “Why write this story?” he wrote. “As each Christmas season approaches, a new version is related. It is always different.”

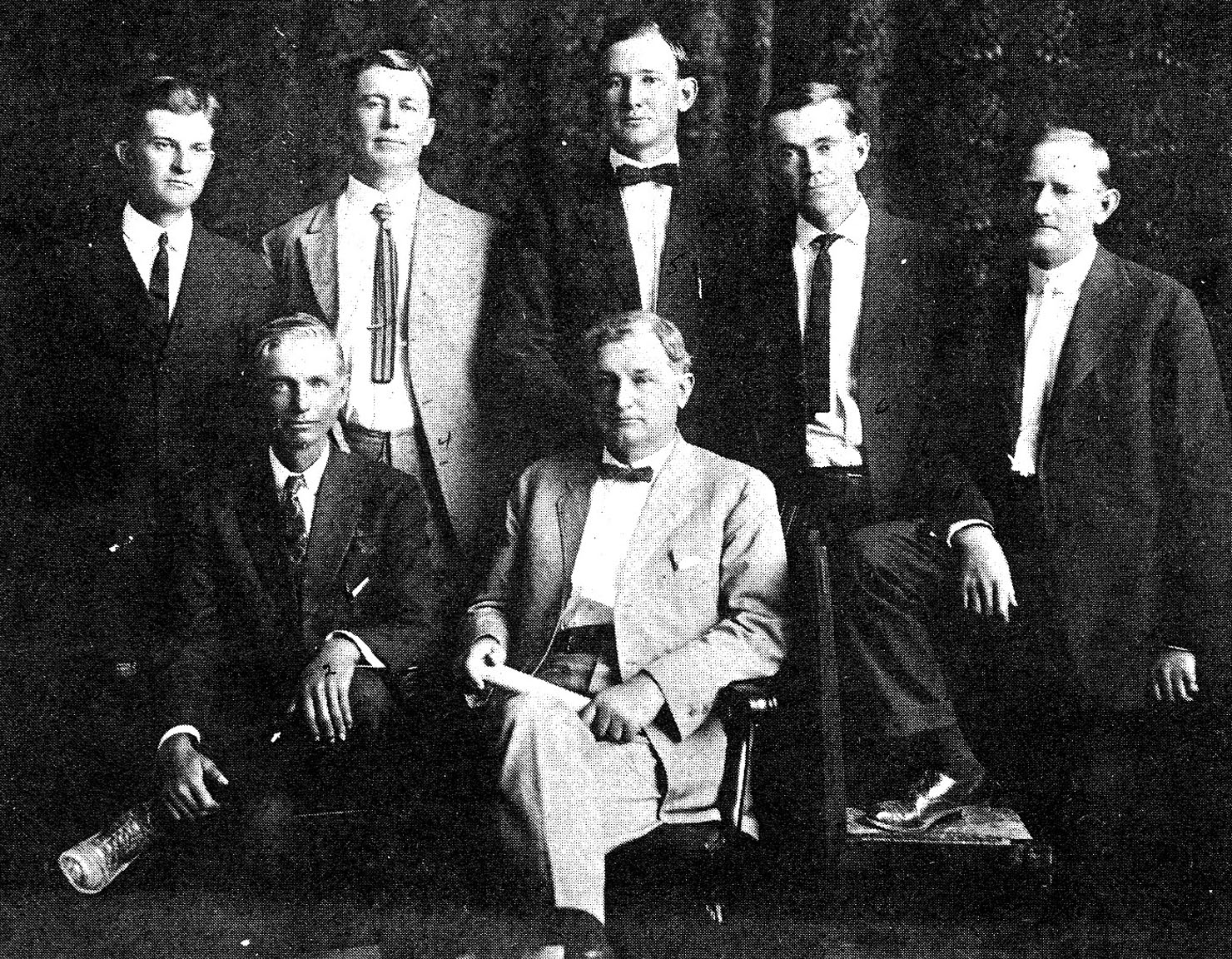

Luckett Bishop is standing left with the other Texas Rangers in Company A. His brother T. S. Bishop would also become a ranger.

While Bishop told the story as best as he remembered it from his father’s viewpoint, In 1939,T.U. Taylor, a university professor who abhorred vigilante justice, told a version sympathetic to one of the six relatives involved in the gun battle. He, too, admitted that after talking to five living witnesses that were at the least present that day, they all gave different versions. Taylor despised the vigilantes for not using the criminal justice system in place in the county at that time. He either did not know about or ignored the violence done to anyone who tried to use the courts to get justice.

T.U. Taylor was the dean of engineering and highly respected during his lifetime. He’s come under scrutiny lately for promoting “The Eyes of Texas,” a minstrel song originally done in blackface. While Taylor deplored what had been more understood fifty years previously, what he had accepted in the mid twentieth century is now frowned upon.

A life-long resident of McDade, Sam Earl Dungan’s answer to my questions stripped away everything and went straight to crux of the matter.

Coming up in Part Four: Who's firing the guns in this reenactment?

Books:

A broke Texas rancher risks all to drive longhorns through the wilds of West Texas to sell to the government in New Mexico, but he’s hindered by the feuding relatives and green cowboys he is forced to hire as drovers.

A BAD PLACE TO DIE and A SEASON IN HELL

Tennessee

Smith becomes the reluctant stepmother of three rowdy stepsons and

the town marshal of Ring Bit, the hell-raisingest town in Texas.

A little boy finds a new respect for his father when he helps him solve a series of brutal murders in a small Texas town.

A

rancher takes his nephews on an adventurous hunt for buried

treasure that lands them in all sorts of trouble.

Two

lonely people hide secrets from one another in a May-December

romance set in the modern-day West.

Short Stories:

WOLFPACK

PUBLISHING - "A

Promise Broken - A Promise Kept"

A

woman accused of murder in the Old West is defended by a

mysterious stranger.

THE UNTAMED WEST – “A Sweet Talking Man”

A sassy stagecoach station owner fights off outlaws with the help of a testy, grumpy stranger. A Will Rogers Medallion Award Winner.

UNDER WESTERN STARS - "Blood Epiphany"

A broke Civil War veteran's wife has left him; his father and brothers have died leaving him with a cantankerous old uncle, and he's being beaten by resentful Union soldiers. At the lowest point in his life, he discovers a way out, along with a new thankfulness. A Will Rogers Medallion Award Winner.

SIX-GUN JUSTICE WESTERN STORIES – “Dulcie’s Reward”

Seventeen-year-old

Dulcie is determined to find someone to drive her cattle to the

new market in Abilene.

"The decision to do a reenactment."

"Doing research for the reenactment."

"Sorting out the truth to make a historically accurate reenactment."

"Who's firing the guns?"

"Finding experienced reenactors."

"Organizing a reenactment - coming down to the wire."

"Rehearsing the reenactment."

"Show time!"